SHORE LAND | GRANT PARK

Transcript © 2023 JeeYeun Lee

KYLE MALOTT: Bodéwadmi kedwen yawen i ‘Chicago.’ Bnëwi shna Bodéwadmik gi byé dnezwêk, Zhegagoynak gi zhnëkadanawa shodë kik. Batinwik zhegagozhik shodë gi mathigék nëko. Wgi pa pkëbnawan ni zhegagozhin gi Bodéwadmik athë mwawat.

Chicago is a Potawatomi word. Long ago up until now Potawatomi have lived here, they called this land Zhegagoynak [place of wild onions]. A lot of wild onions grew in this area at one time. The Potawatomi would go about picking wild onions in order to eat.

Articles of a treaty made at Chicago in the state of Illinois on the 26th day of September, in the year of our Lord 1833, between Commissioners on the part of the United States and the United Nation of Chippewa, Ottowa, and Potawatamie Indians, being fully represented by the Chiefs whose names are hereunto subscribed. Article First. The said United Nation of Chippewa, Ottowa Potawatamie Indians cede to the United States all their land along the western shore of Lake Michigan, and between this Lake and the land ceded to the United States by the Winnebago nation at the Treaty of Fort Armstrong, bounded on the north by the country lately ceded by the Menominees and on the south by the country ceded at the Treaty of Prairie du Chien, supposed to contain about five millions of acres.

MADOLYN WESAW: Boozhoo. <Introduction in Potawatomi>. Hello, my name is Madeline Wesaw. I am Turtle Clan, I’m a member of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi, and I come from St. Joseph, Michigan. The Potawatomi homelands, it’s the entire Great Lakes region. Historically, Potawatomi people would have been up into Wisconsin and Canada and Illinois and Indiana, all around Lake Michigan, extending out into Ohio and a little bit further. We’ve always been around the water, that’s always been significant for our people, that we are where the water is at.

It being understood that the said Indians are to remove from all that part of the land now ceded, which is within the state of Illinois, immediately on the ratification of this treaty. In testimony whereof, the said George B. Porter, Thomas J. V. Owen, and William Weatherford, and the undersigned chiefs and head men of the said nation of Indians, have hereunto set their hands at Chicago. G. B. Porter, J. V. Owen, William Weatherford, To-pen- e-bee, his x mark, Ob-wa-qua-unk, his x mark, N-saw-way-quet, his x mark, Puk-quech-a-min-ee, his x mark, Nah-che-wine, his x mark ...

MADOLYN WESAW: My grandfather was a residential school survivor. His mother before him was also. The intention, the goals of these schools was to kill the Indian to save the man. The children, if they were caught speaking our language, they would be beaten and tortured. You’ll hear stories of survivors where they talk about witnessing their siblings and other children being severely punished for being caught speaking their language. It was instilled in them from a very young age that it was actually a shameful and a really negative thing to speak their language. Our connection to our language and to who we were as Anishinaabe people was really effectively severed in a lot of ways.

Ke-wase, his x mark, Wah-bou-seh, his x mark, Mang-e-sett, his x mark, Caw-we-saut, his x mark...

MADOLYN WESAW: Towards the end of my grandfather’s life, and at this time, we had no idea about his history at the Mount Pleasant residential school. He never spoke of it to any of us. I had this conversation with him, where he had told me that it was really important for me to remember no matter what, that I’m an Indian woman, Anishinaabekwe, and he said, they’re gonna try to take that from you, but you can’t let them.

Ah-be-te-ke-zhic, his x mark, Pat-e-go-shuc, his x mark, E-to- wow-cote, his x mark, Shim-e-nah, his x mark...

MADOLYN WESAW: I grew up and I became a mother myself and I started to really understand the importance of not just knowing where I come from, but that these things, as an Anishinaabe person, are my birthright. Recovering my language and my traditions has been a journey. This is the language that our ancestors spoke, and when we speak it, they can hear us and they’re so proud and they’re here with you and, and you can feel some of that power when you speak your language. I have a responsibility not just to myself but to my son and the next seven generations to keep that knowledge.

KYLE MALOTT: Manék Bodéwadmik shodë gi dnezwêk nëko. Thimanen wgi yonawan athë pambeshkawat minė athë gigokéwat. Shodë mbesek minė gé zagthëwnak gathë gigokéwat. Wigë gigoyen wgi sbyénawan minė wgi gwdëmonawan. Manék gigoyêk dnezwêk nambik shodë ktthegmik. Shëgnêk, nmégwzéyêk, mazhmékwséyêk, wasiyêk, nmébnék, angodogawék, mskigwék, namék, genozhék, gwedashiyêk, ogak, adikmëgok, sawék, gnébgomëgok, mine wigë gigozésêk yéwik.

A lot of Potawatomi used to live here at one time. They used canoes in order to travel on water & also to fish. Here at the lake and at the river outlet is where they fished. They would catch all kinds of different fish via nets and hooks. Bass, Lake Trout, Trout, Catfish, Sucker fish, Carp, Crappie, Sturgeon, Northern Pike, Bluegill, Walleye, Whitefish, Perch, Eel, and all kinds of little fish.

MADOLYN WESAW: Lake Michigan in particular provides for our people in a lot of ways, so we’ve always lived near it. And we’ve always traveled to different parts of it for different seasons. Wild Rice, which is important in our culture, minoomin, grows in the water. So one of the most important parts of our diet grows in the water and we spend all of our time on or near the water. Water is as much our home as this land is.

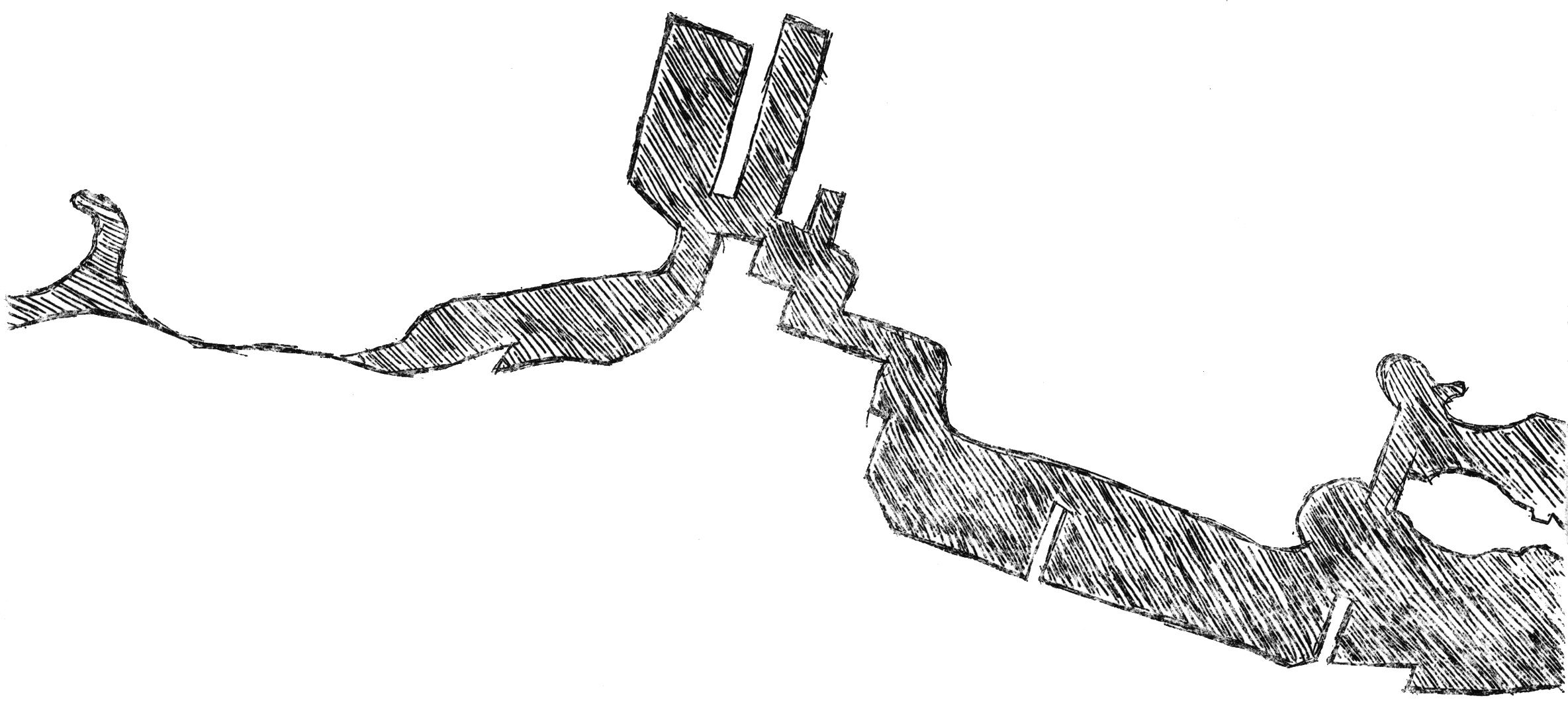

Chief Williams et al. v. City of Chicago et al., US Supreme Court, 1917. Complainants are eight Potawatomi Indians, members of the Pokagon band and residents of Michigan. Defendants are the city of Chicago and certain corporations now occupying valuable lands within the geographical limits of Illinois, which have been reclaimed from Lake Michigan. The Potawatomi Indians were the owners and in possession as a sovereign nation of large tracts of land around and along the shores of Lake Michigan, south of a line running from Milwaukee River, Wisconsin, to Grand River Michigan, and extending“east and west of said two points, and including all of Lake Michigan, which is south of said line.” By later treaties, the Potawatomi Nation re-ceded to the United States all such lands up to the shores of Lake Michigan, but those within the geographical limits of Illinois, which were formerly beneath the waters of Lake Michigan, “whether reclaimed, artificially made or now or formerly submerged, have remained and still or the property of these complainants and any attempts on the part of any persons, firms and corporations to appropriate the same or any part thereof, were and are in violation of set treaties and of the rights of these complainants.” The only possible immemorial right which the Potawatomi Nation had in the country claimed as their own was that of occupancy. If in any view it ever held possession of the property here in question, we know historically that this was abandoned long ago, and that for more than a half century, it has not even pretended to occupy either the shores or waters of Lake Michigan within the confines of Illinois.

MADOLYN WESAW: These lands have always provided for our people, and they’ve helped to sustain us, and we have always, in turn, taken care of this land and given back to this land and to this water. It’s interesting as a Potawatomi woman to be in cities like Chicago, which are our homelands. And we are treated almost as second class citizens or like invaders and intruders in our own homeland. We have a claim to these lands, not just historically, not just ancestrally, but legally, according to your own government and your own laws. We have a right to this place.

The ownership of and dominion and sovereignty over lands covered by tidewaters belong to the respective states within which they are found. It is a title held in trust for the people of the state, that they may enjoy the navigation of the waters, carry on commerce over them and have liberty of fishing therein. The state can no more abdicate its trust over property in which the whole people are interested, like navigable waters and soils under them so as to leave them entirely under the use and control of private parties, than it can abdicate its police powers in the administration of government and the preservation of the peace. Such abdication is not consistent with the exercise of that trust, which requires the government of the state to preserve such waters for the use of the public. The idea that its legislature can deprive the state of control over its bed and waters and place the same in the hands of a private corporation is a proposition that cannot be defended.

Approved July 27, 1896. Be it ordained by the City Council of the City of Chicago that consent is hereby given to the South Park Commissioners to take, regulate, control, and govern all that park known as the Lake Front Park or Lake Park, except, however, that portion lying north of the north line ... (obscured by overlapping voices and waves) ... the Illinois Central Railroad Company’s right of way, and west of the right of way of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, including in the consent hereby given all land which may be hereafter reclaimed adjoining said Park. And the said South Park Commissioners shall have the right to control, improve, and maintain so much of the said Park as it is hereby authorized to take.

Plan of Chicago, prepared under the direction of the Commercial Club, by Daniel H. Burnham and Edward H. Bennett, 1909. The lakefront by right belongs to the people. It affords their one great unobstructed view, stretching away to the horizon, where water and clouds seem to meet. These views of a broad expanse are helpful to mind and body. They beget calm thoughts and feelings. Mere breadth of view, however, is not all. The lake is living water, ever in motion, and ever changing in color and in the form of its waves. Across its surface comes the broad pathway of light made by the rising sun. It mirrors the ever changing forms of the clouds and it is illumined by the glow of the evening. Its colors vary with the shadows that play upon it. In its every aspect, it is a living thing, delighting man’s eye and refreshing his spirit.

LEANNE BETASAMOSAKE SIMPSON: (Introduction in Anishinaabe). I’m a Mississauga Anishinabek, and our territory is on the north shore of Lake Ontario. For us, this stolen piece of wilderness for Mississauga people is the Kawartha Highlands Signature Park, which is this piece of 375 square kilometers of wilderness about 50 kilometers north of Peterborough. And the elder that I work with believes very strongly that this area should be given back to us. His grandfather’s trap line and hunting grounds are in this area, and it’s been in his family for generations. He also believes very strongly that the province has designated his a provincial park to alienate Anishinabek people from our settler allies, who very much enjoy camping and canoeing and kayaking in the park. And so my elder thinks that by designating the very few wilderness areas that we have left in the province as a protective area, that Ontario doesn’t have to worry about resistance, because this tiny group of settlers that supports us will not support us gaining land that is designated as a protected area. They believe that because it’s part of the commons, that Anishinabek have the same rights as Canadians to use the park. And I think there’s a lot of truth in this elder’s thinking, because what he’s saying is that this idea of commons erases Anishinabek nationhood, erases our self determination, our sovereignty and our land rights. It maintains our dispossession in a way that is acceptable to many of our settler allies because we can all use the land.

– Ieodo Sana folk song in Korean –

City of Chicago v. Ward et al., Supreme Court of Illinois, 1897. This was a bill for an injunction by A. Montgomery Ward and George R. Thorne to enjoin the city of Chicago from erecting any buildings on what is known as Lake Park or Lake Front Park. The bill alleges that they are the owners of the south 43 feet of lot 3, and all of lots 4 and 5, in block 15 in Fort Dearborn addition, that when said addition was platted, an open space was reserved for public grounds east of Michigan Avenue, subject to the prohibition that the grounds should be kept free from buildings, that the lots owned by them are worth more on account of such vacant grounds than they would be otherwise....

Bliss et al. v. Ward et al., Supreme Court of Illinois, 1902. An open space was reserved for public ground east of Michigan Avenue, by means of the words marked on the plat: “Public ground forever to remain vacant of buildings.” We are of the opinion that when the limits of the park were extended into the lake, no right was acquired to erect buildings between the lots and the lake. And that the park....

Ward v. Field Museum of Natural History et al., South Park Commissioners v. Ward et al., Supreme Court of Illinois, 1909. This suit is a renewal of a controversy of long standing between Montgomery Ward and the public authorities having the control and management of what is now known as Grant Park. The third bill for the protection of his rights to have the park kept free from building was filed by Ward against the Field Museum of Natural History, praying for an injunction restraining the construction and erection of said building, or any building, impairing or obstructing his easement. Under the dedication....

South Park Commissioners v. Montgomery Ward and Company et al., Supreme Court of Illinois, 1910. The South Park Commissioners appealed from four judgments of the Superior Court of Cook County. It was determined in each case that Ward occupied a position which gave him a right to enforce the restriction as one having a special interest in having it enforced. It was decided in the previous suits that there was no lawful authority for the erection of buildings in Grant Park. And without such authority, there could be no valid law authorizing the condemnation of property....

MADOLYN WESAW: Historically, this land has always been very significant for our people. Indigenous people and Potawatomi people, we talk about wanting to return to our homelands and to be able to have stewardship to take care of our homelands. Because the colonial mindset is very much an us versus them, they can’t fathom that there’s a way for both, for everybody to succeed and live healthy lives here. To them, to return stewardship of the land to its Indigenous inhabitants would mean a destruction of their way of life, and they can’t see it any other way.

The Lakefront Plan of Chicago, 1972. Lake Michigan and Chicago share a unique and historic relationship. The lakefront has been the landing place for explorers, fortress for the frontier, location for great international expositions, and a transportation route for the wealth of the Midwest. It has become one of the great recreational and cultural resources of the world. New knowledge about the lake itself, its natural forces and its ecology, makes it possible for us to plan and design for the future. We can add to the lakefront, and at the same time, make sure that what we build contributes to a harmony between Chicago and the great natural environment of the lake, and assures an ordered and humane development. Chicago’s lakefront must ever be preserved for public use and enjoyment. We must do all in our power to protect this great natural asset for ourselves and for future generations. Richard J. Daley, Mayor.

Grant Park Framework Plan, Chicago Park District. Grant Park is Chicago’s central civic open space and the keystone of Chicago’s extensive lakefront park system. It represents the synthesis of Chicago’s civic integrity, its cultural development, and its greatest natural resource, Lake Michigan. People are drawn to the diverse amenities and unique setting of this great urban park – Lake Michigan, the Clarence Buckingham Memorial Fountain, grand vistas of the city and lake, and impressive museums. As the city continues to flourish, particularly in the central area, the demand for Grant Park to parallel this progress intensifies. These changes necessitate a framework plan that weaves historical elements, current demands, and projected needs into a single vision for the future of Grant Park.

– Ieodo Sana folk song in Korean –

KYLE MALOTT: Mnedo gé wi dnezé shodë ktthegmik, ė kowabdêk odë mbes, nambezho zhenkazé. Byé bgednawan ni séman gi Bodéwadmik shodë ktthe gmik ėwi gaténmawat ni nambezhoyen. Bmadzëwen yawen i mbish. Abdék shna ginan gda bméndamen odë mbish athë mnobmadzëygo. Gwi bménmëgomen gishpen këwabdëmgo odë kė.

There’s also a spirit that lives here in this lake and he watches over this lake, known as the Underwater Panther. Potawatomi people come and place tobacco to show respect to the Underwater Panther. Water is life. We all have to take care of the water in order to have good health. If we take care of the earth, we will be taken care of.

MADOLYN WESAW: So as an Anishinaabe woman, I was taught that my relationship to the water is special. Women bring forth life into this world, within our wombs, and we sustain that life with water within our bodies. Me in particular, I am mshiké dodém, I am Turtle Clan. And that means that it is my job, also my responsibility and role within my community, to protect

and to care for the water. And not just in a way that takes but

in a way that also gives back to that water. There has to be a balance. We as human beings need water in order to survive. But in order for us to be able to use that water, we have to protect it, we have to respect it and honor it. As a Potawatomi woman, essentially my relationship with that water is based on a love and respect that is mutual.

– Nibi Water Song in Anishinaabe –